Random thoughts about roadside art, National Parks, historic preservation, philosophy of technology, and whatever else happens to cross my mind.

Sunday, March 27, 2011

Book Review: Superbug

I hear a lot of doom and gloom when I'm listening to the news: wars, and rumors of wars, nuclear meltdowns, global warming, economic meltdowns. . .

I hear a lot of doom and gloom when I'm listening to the news: wars, and rumors of wars, nuclear meltdowns, global warming, economic meltdowns. . . I read a lot of scary stuff at work: case studies of patients who die from exotic fungi that fill their lungs with furballs, for example, or have their brains eaten by amoeba, but none of those case studies ever made as much of an impression as the book Superbug. A case here, a case there, and it doesn't really sink in, especially when, as Maryn McKenna notes, the medical community as a whole spent quite a few years in denial when it came to the issue of community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections.

The journal I work for actually ran a review of Superbug back in October or so; I wasn't involved in the editing for it so didn't pay much attention to it at the time. I did recall that the reviewer wasn't too impressed with the book, said it was overly melodramatic and the author didn't understand the complexities of MRSA. Now that I've read the book, I understand the reviewer's hostility better. He should have declined to do the review -- his hospital is one that has a starring role in the book for using highly unsanitary practices on its obstetrics ward and for putting one of the patients profiled in the book through what can only be described as living hell. That particular hospital was also one that responded to the patient's concerns in sadly typical fashion: the infection didn't flare up until you were home, so you didn't catch it from us. The reviewer definitely, at least by association, falls into the group that McKenna is criticizing for doing too little, too late.

Superbug is actually meticulously researched. McKenna names names -- doctors, hospitals, patients -- and it's pretty clear that some of the material being presented had the potential to generate lawsuits if the proper documentation didn't exist to back it all up. Clinicians and hospitals may be unhappy about some of McKenna's findings, but to call them "melodramatic" or unfounded is an exercise in wishful thinking. Someone being hospitalized repeatedly for an infection that won't go away and then finding out after the 7th or 8th hospitalization that the doctors had been using the absolutely wrong drug as part of the treatment regimen isn't melodrama -- it's tragedy. In example after example, patients come in with an infection and the physicians treat it empirically (i.e., they don't run lab tests to find out exactly what the bug is; they just treat the symptoms with drugs that have worked in the past for complaints that looked similar) (McKenna doesn't talk about why, but a lot of empirical treatment is insurance driven -- physicians are reluctant to order tests an insurance company won't pay for). So they start off with a type of penicillin. It doesn't work. So then they go for methicillin. It doesn't work. And they keep doing it, working their way up the chain to the most recent antibiotics in that same class of drugs -- and nothing works, but they don't want to admit they've been screwing up, especially when MRSA's been around for quite a few years now.

Bacteria mutate fast, and staph is no exception. Methicillin was developed fifty years ago because S. aureus became penicillin-resistant pretty quickly. Unfortunately, S. aureus than became methicillin-resistant. And resistant to a whole lot of other antibiotics that all worked on the same principle as either penicillin or methicillin. That was the bad news. The good news was that MRSA was rarely seen outside a hospital setting. If someone came down with a MRSA infection, they almost always picked it up in a hospital. That changed in the 1990s. Patients started popping up who didn't fit the profile. So what did the medical establishment do when confronted with the possibility of community-acquired MRSA? They ignored it. They pretended it couldn't be happening. The first few published reports describing MRSA happening outside hospitals were either discounted or ignored. It took several high profile outbreaks to get the medical community to really sit up and take notice -- but it may already be too late.

As McKenna tells us, not only has MRSA managed to evolve into multiple strains, some of which are incredibly virulent, with each new antibiotic tossed at it, seems to develop resistance faster. Even worse, the pharmaceutical companies have figured out there's not much money to made in antibiotics, so there aren't many new ones under development. The big bucks for Big Pharma are in the drugs that people have to take for chronic conditions, like Lipitor for high cholesterol. Antibiotics are short term, a few weeks, a month, and the patient is done. Lipitor is forever.

In short, MRSA has evolved into a pathogen that's resistant to almost everything modern medicine can throw at it, the various strains are spreading (and in many cases how and why is a complete mystery to the epidemiologists), and there is no silver bullet waiting in the wings.

According to McKenna, and I tend to agree with her, we brought MRSA on ourselves. We've abused antibiotics, demanded them from our doctors to treat conditions that aren't treatable with antibiotics (like the common cold), taken them improperly (e.g., stopped taking them as soon as symptoms got better), allowed them to be dumped into the environment, and generally set up conditions that guaranteed they weren't going to be much use for very long. Along the way, we've also gotten remarkably careless about the things we used to do before we assumed there was a cure for everything, like handwashing. We went from figuring out germ theory to being fanatics about handwashing and strict hygiene in healthcare settings back to being remarkably careless in barely 100 years. We also engage in contradictory behaviors like spritzing kitchen counters with bleach while at the same time doing our laundry in cold water, so we're killing bacteria in one place while ignoring them in another.

I'm not quite sure what the take-away message is in Superbug. You can't fool Mother Nature? Technology always has unintended consequences? We're fucked?

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Not a happy camper

I just reset the countdown clock. For a number of reasons, it appears we won't be loading the U-Haul and seeing Georgia in the rear view mirror quite as soon as the S.O. and I had been hoping.

I definitely have mixed feelings about lingering in Atlanta. Living in a state that seems intent on proving that every stereotype about ignorant rednecks is true does get old after awhile. Everytime I think the good ol' boys under the Gold Dome have managed to come up with the World's Dumbest Idea, they top themselves. Maybe it's something in the fertilizers they use on the peanuts?

On the other hand, and in a feeble attempt to look on the bright side, there is Mexican Coca-Cola being sold within walking distance of our apartment, and it's a lot easier to shovel pollen than it is to shovel snow.

I definitely have mixed feelings about lingering in Atlanta. Living in a state that seems intent on proving that every stereotype about ignorant rednecks is true does get old after awhile. Everytime I think the good ol' boys under the Gold Dome have managed to come up with the World's Dumbest Idea, they top themselves. Maybe it's something in the fertilizers they use on the peanuts?

On the other hand, and in a feeble attempt to look on the bright side, there is Mexican Coca-Cola being sold within walking distance of our apartment, and it's a lot easier to shovel pollen than it is to shovel snow.

Monday, March 21, 2011

That time of year again

Went out to head for work this morning and discovered my formerly white car had become chartreuse overnight. The pine trees are definitely blooming. Fairly soon the drifts will start forming and folks will have to break out the Georgia equivalent of snowshoes in order to cope.

Saturday, March 19, 2011

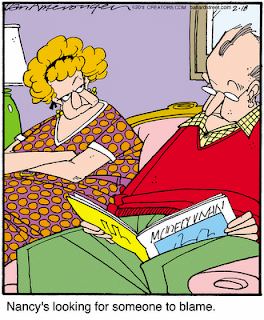

Pulitzer Project: Honey in the Horn

Another odd book, and, believe it or not, the pulp edition cover art does actually match up with the action in one of the chapters. Sort of.

Honey in the Horn won the Pulitzer for a novel in 1936. It's not a bad book, although it reads like an odd hybrid of Zane Grey and Mark Twain. The novel is set in the Pacific Northwest around the beginning of the 20th century. The first few chapters with their descriptions of frontier life -- rough wagon roads, everyone getting around by horseback or on foot, the movement of would-be settlers and migrant farm workers (e.g., hops pickers) by wagon -- had me thinking 1880s, maybe 1890s, but then about midway through there's mention of E. H. Harriman's automobile, which would make it the early 1900s. Harriman died in 1909.

The plot, such as it is, revolves around a teenager, Clay, who is the not particularly bright foster son of a local rancher/farmer who operates a stage station. Clay kind of blunders his way through lfe -- has good luck when he's not trying at all, but then gets to see things turn weird on a regular basis for no apparent reason, usually when he's trying to do what he thinks is the right thing. He falls into a relationship with a horse-trader's daughter (she's the one in the bloomers on the cover), and spends 300 pages believing he needs to protect her. (He's wrong, of course.) Along the way, he encounters various restless Americans, all of them thinking the next big chance is going to happen wherever they move to next. He goes from his home ranch into hops-growing country, picks hops for awhile, and then ends up heading west to the Oregon coast near Coos Bay. After spending the winter there, he joins a group of disgruntled settlers who had decided the coast wasn't all it was cracked up to be, and were aiming to settle on the dry side of the mountains (eastern Oregon).

He then wanders east, doing various odd jobs along the way, and eventually ends up in northern Nevada. He and the girlfriend part company for a few chapters, so he spends his spare time obsessing about her. Eventually they're re-united, they vow never to part or keep secrets from each other again -- and right about the time he's realizing he's hooked up with Caril Ann Fugate, the book ends.

I'm not sure just what the point of Honey in the Horn was, or if there even is one. There is a distinct "there's no place like home" undertone to it, as Clay finds himself thinking on a regular basis that the one place he really wanted to be (the stage station) is now the one place he can never go back to. There's also a fair amount of mockery of Americans with their restlessness and get rich quick schemes -- Clay passes through a number of "towns" where someone has platted 40 acres of desolate sagebrush into a town-site, complete with a name like Appledale and lots labeled "opera house" or "mercantile," all in the hopes of suckering people into buying land there on the prospects of the railroad going through.

The novel is well-written. The language is colorful, the descriptions of everyday life in frontier communities is realistic, there's a fair amount of humor and good-natured mockery of human foibles, and there's no moralizing. Stuff happens, people have regrets, but life goes on. This wasn't the best of the winners I've read so far, but it definitely falls into the top half of the pack -- it was worth the $3 interlibrary loan fee.

Next up on the list for 1937 is Gone with the Wind. It's been quite a few years since I read it, but I think I'll skip over it anyway to 1938 and The Late George Apley. I loved Gone with the Wind when I read it in high school; I'd hate to read it now and be appalled by it turning out to be absolute dreck.

Honey in the Horn won the Pulitzer for a novel in 1936. It's not a bad book, although it reads like an odd hybrid of Zane Grey and Mark Twain. The novel is set in the Pacific Northwest around the beginning of the 20th century. The first few chapters with their descriptions of frontier life -- rough wagon roads, everyone getting around by horseback or on foot, the movement of would-be settlers and migrant farm workers (e.g., hops pickers) by wagon -- had me thinking 1880s, maybe 1890s, but then about midway through there's mention of E. H. Harriman's automobile, which would make it the early 1900s. Harriman died in 1909.

The plot, such as it is, revolves around a teenager, Clay, who is the not particularly bright foster son of a local rancher/farmer who operates a stage station. Clay kind of blunders his way through lfe -- has good luck when he's not trying at all, but then gets to see things turn weird on a regular basis for no apparent reason, usually when he's trying to do what he thinks is the right thing. He falls into a relationship with a horse-trader's daughter (she's the one in the bloomers on the cover), and spends 300 pages believing he needs to protect her. (He's wrong, of course.) Along the way, he encounters various restless Americans, all of them thinking the next big chance is going to happen wherever they move to next. He goes from his home ranch into hops-growing country, picks hops for awhile, and then ends up heading west to the Oregon coast near Coos Bay. After spending the winter there, he joins a group of disgruntled settlers who had decided the coast wasn't all it was cracked up to be, and were aiming to settle on the dry side of the mountains (eastern Oregon).

He then wanders east, doing various odd jobs along the way, and eventually ends up in northern Nevada. He and the girlfriend part company for a few chapters, so he spends his spare time obsessing about her. Eventually they're re-united, they vow never to part or keep secrets from each other again -- and right about the time he's realizing he's hooked up with Caril Ann Fugate, the book ends.

I'm not sure just what the point of Honey in the Horn was, or if there even is one. There is a distinct "there's no place like home" undertone to it, as Clay finds himself thinking on a regular basis that the one place he really wanted to be (the stage station) is now the one place he can never go back to. There's also a fair amount of mockery of Americans with their restlessness and get rich quick schemes -- Clay passes through a number of "towns" where someone has platted 40 acres of desolate sagebrush into a town-site, complete with a name like Appledale and lots labeled "opera house" or "mercantile," all in the hopes of suckering people into buying land there on the prospects of the railroad going through.

The novel is well-written. The language is colorful, the descriptions of everyday life in frontier communities is realistic, there's a fair amount of humor and good-natured mockery of human foibles, and there's no moralizing. Stuff happens, people have regrets, but life goes on. This wasn't the best of the winners I've read so far, but it definitely falls into the top half of the pack -- it was worth the $3 interlibrary loan fee.

Next up on the list for 1937 is Gone with the Wind. It's been quite a few years since I read it, but I think I'll skip over it anyway to 1938 and The Late George Apley. I loved Gone with the Wind when I read it in high school; I'd hate to read it now and be appalled by it turning out to be absolute dreck.

Friday, March 18, 2011

No ambition

Maybe it's the lingering effects of the "spring ahead" nonsense with the clock, but I've spent the whole week feeling like I'm only half awake. No ambition whatsoever, and definitely feeling brain dead.

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Saturday, March 12, 2011

Anyone for a burger with a side of E. coli?

The Blog Fodder had a post the other day about meatless Mondays at Bowdoin College in Maine. It got me to thinking about farming, food production, and cattle as an environmental issue, but naturally not in any sort of logical fashion. Instead I started thinking about nonpoint source pollution, the Shenandoah valley, and cow pies.

Back when I was in grad school, I spent a semester hanging out with agricultural engineers. Okay, I wasn't really hanging out -- I was completing a class assignment in qualitative research by doing a participant-observation study of identify formation within a particular profession. (I even got a published -- sort of [do conference proceedings count?] -- paper out of the experience: "Nobody Knows Who We Are: A Participant-Observation Study of an Agricultural Engineering Seminar"). Margaret Mead got to go to Samoa; I walked across the drill field to the Ag quad and sat in a seminar series sponsored by the ag engineering program at VaTech. It was fun. I came close to going native -- the ag engineers had some of the same problems we poor saps in Science and Technology Studies did (e.g., no respect). I learned all sorts of nifty bits of trivia, most of which I've managed to forget, although the presentation on Monte Carlo modelling to calculate how many cows you could graze on a field that drained into the Shenandoah and not create a health hazard did stick in my mind, even if I can't remember the answer. I also stumbled across some interesting tidbits in the history of technology that I thought would make great thesis topics. My committee had different ideas.

One of those topics was, in essence, the history of getting shit out of the barn. Literally. Dairy cattle used to be routinely confined to stalls for milking, first with cow chains (we still have cow chains hanging in our barn up on the tundra) and later with stanchions. Only one problem: cattle shit. Cattle shit a lot. They don't process grass quite as fast as geese, but they come close. So how do you deal with all that crap? For many, many years the answer was "gutters." You built a trench into the barn floor that would (hopefully) catch most of the fecal material and liquid waste. The liquid would run down the gutter and out; the more solid waste would get shoveled. Nineteenth century agricultural journals were full of designs for barn floors that had the ideal gutter shape and slope. Shovels were carefully crafted to fit the gutters just right -- and then someone had the brilliant idea of mechanical gutter systems, conveyors that would move the shit out the door and on to the manure heap. I really, really wanted to do a thesis on the history of barn cleaners; my committee said, in essence, "Shit? No." Anyway, year after year, decade after decade, the journals touted various mechanical gutter cleaning systems, zillions of patents got filed, and then. . . the ultimate breakthrough.

How about if instead of getting the shit out of the barn, they took out the cows and eliminated the barn? Enter the milking parlor: cows walked in, stood in one spot long enough to get milked, and walked out again. Instead of being in stalls waiting their turn, the beasts got to mill around on concrete pads that could be cleaned with a blade on a tractor or with a pressure hose and water.

On one level, this was brilliant. On another? Well, one of the basic laws of technology is that every innovation has consequences, some good, some bad. One of the effects of just about every innovation in agriculture has been to increase the costs of doing business: the guy with the shovel was a much lower initial investment than the mechanical gutter cleaner, and the gutter cleaner cost less upfront than putting in a milking parlor, just like milkmaids with pails were a much lower investment than a Surge milking system. You start getting into economies of scale that require more livestock in order to break even. Herd size grows, various costs go up, profit margins shrink -- it's amazing anyone still wants to farm, especially on the industrial scale required today in order to be in compliance with various state and federal regulations.

And what does all this have to do with the title of the post? Short verison: the more cattle (or hogs or chickens or livestock of any sort) you have to put together in one small space in order to make a profit from "farming," the bigger the pile of shit is going to be. That shit has to go somewhere -- and where it too often ends up is in rivers, lakes, and irrigation canals. A particularly virulent serotype of E. coli happens to enjoy living in cattle guts -- cattle shit pollutes irrigation ditch, irrigation water gets sprayed on lettuce, and, voila, you get served shiga toxin producing E. coli O157 with your salad.

It really is a testament, in a weird way, to the efficiencies of our modern, highly industrialized food production system that E. coli are able to go from cattle gut to lettuce field to human consumption sufficiently quickly for the bacteria to still be viable. Coliform bacteria are anaroebic -- a couple days out in the open, exposed to sunlight and air, and they're dead.

So, yep, the kids at Bowdoin are right: cattle are an environmental problem. They're also a public health problem. Will meatless Mondays change that? I doubt it, but at least I understand some of the reasoning behind the attempt -- and when we have steak, maybe I'll skip the salad on the side.

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Sunday, March 6, 2011

I can't believe I did this

I set the alarm clock on a Saturday night. The alarm went off at its usual time, and I went into automatic pilot mode: got up, stumbled around, turned on the coffee pot, and was muttering to myself about how fast the weekends go. Then I turned on the tv to see what Karen Minton had to say about the weather, and there was some Bible-thumper exhorting me to find the Lord now. Does "Holy crap! It's Sunday! Why am I up?!" count as seeing the light?

The topic of the moment on C-SPAN is education -- who should control it? Feds? State? Strictly local? If we were a sane nation (and we all know we're not), it would be the feds. Why? Consistency, both in content and in quality. A national common curriculum would help ensure that a kid graduating from high school someplace out BFE, Idaho, would have the same basic set of skills and knowledge as a kid graduating from high school in Tampa, Florida, or Portland, Maine. That definitely isn't true now. There are regional accreditation organizations, but how well they function is debatable -- and, unlike almost every other country on the planet, accreditation agencies are nongovernmental. States do set basic standards for accreditation, but those standards can vary widely, depending on who happens to be on the state school board in any given year. In some states, school boards are elected; in others, they're political appointees of the governor. Both are methods guaranteed to produce boards that can swing wildly from one extreme to the other when it comes to what it gets taught and how.

And then when you get down to the local level, which is where schools are actually controlled in the United States. . . local school boards are notorious for stupidity. Because members are elected, it is quite possible for one particular faction in a community that has an ideological agenda of some sort to end up packing a board. End result? School boards can be appallingly incompetent or ideologically driven, either one being a litigation magnet. Even when examples are trotted out, like the Dover case, to explain why a particular idea, like teaching creationism, is going to do nothing but provide job security for attorneys, the ideologically driven will plow right ahead and insist that the school do it anyway.

And then there's the dumb stuff growing out of wanting to do someone a favor. One local school board back in the UP, for example, decided to hire a former supermarket manager as its new superintendent rather than go with any of the candidates who actually had some experience in education. Why? He was local, he knew the guys on the board, and he was at loose ends because he'd recently sold his business. Of course, then the school district had to pony up the money to pay for the guy to pursue the graduate education and various certifications the state requires for school administrators or risk losing the district's accreditation -- but, hey, why shouldn't someone who's supervised baggers be able to tell teachers what to do?

Then when you get into what actually is or is not being taught in the classrooms. . . One of the reasons I decided there was no way I was ever going to let my kids attend school in a particular district in the UP was I found out the board had decided to razor-blade out all the chapters in science text books that discussed human reproduction or evolution. Yep, ignoring evolution is really going to help the kids from that district a lot when they get into their first college biology class and discover there's a huge hole in their basic education. As for the eliminating the human reproduction material. . . I know correlation isn't causation, but that same district has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates in the country.

In any case, having moved around a lot and as a parent witnessed multiple school districts, from the huge (Los Angeles metropolitan district) to the small (Houghton, Michigan), one thing I know for sure is there is absolutely no consistency in what gets taught, when it gets taught, or how. Local control as currently practiced obviously isn't working, so maybe it's time to try something different.

The topic of the moment on C-SPAN is education -- who should control it? Feds? State? Strictly local? If we were a sane nation (and we all know we're not), it would be the feds. Why? Consistency, both in content and in quality. A national common curriculum would help ensure that a kid graduating from high school someplace out BFE, Idaho, would have the same basic set of skills and knowledge as a kid graduating from high school in Tampa, Florida, or Portland, Maine. That definitely isn't true now. There are regional accreditation organizations, but how well they function is debatable -- and, unlike almost every other country on the planet, accreditation agencies are nongovernmental. States do set basic standards for accreditation, but those standards can vary widely, depending on who happens to be on the state school board in any given year. In some states, school boards are elected; in others, they're political appointees of the governor. Both are methods guaranteed to produce boards that can swing wildly from one extreme to the other when it comes to what it gets taught and how.

And then when you get down to the local level, which is where schools are actually controlled in the United States. . . local school boards are notorious for stupidity. Because members are elected, it is quite possible for one particular faction in a community that has an ideological agenda of some sort to end up packing a board. End result? School boards can be appallingly incompetent or ideologically driven, either one being a litigation magnet. Even when examples are trotted out, like the Dover case, to explain why a particular idea, like teaching creationism, is going to do nothing but provide job security for attorneys, the ideologically driven will plow right ahead and insist that the school do it anyway.

And then there's the dumb stuff growing out of wanting to do someone a favor. One local school board back in the UP, for example, decided to hire a former supermarket manager as its new superintendent rather than go with any of the candidates who actually had some experience in education. Why? He was local, he knew the guys on the board, and he was at loose ends because he'd recently sold his business. Of course, then the school district had to pony up the money to pay for the guy to pursue the graduate education and various certifications the state requires for school administrators or risk losing the district's accreditation -- but, hey, why shouldn't someone who's supervised baggers be able to tell teachers what to do?

Then when you get into what actually is or is not being taught in the classrooms. . . One of the reasons I decided there was no way I was ever going to let my kids attend school in a particular district in the UP was I found out the board had decided to razor-blade out all the chapters in science text books that discussed human reproduction or evolution. Yep, ignoring evolution is really going to help the kids from that district a lot when they get into their first college biology class and discover there's a huge hole in their basic education. As for the eliminating the human reproduction material. . . I know correlation isn't causation, but that same district has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates in the country.

In any case, having moved around a lot and as a parent witnessed multiple school districts, from the huge (Los Angeles metropolitan district) to the small (Houghton, Michigan), one thing I know for sure is there is absolutely no consistency in what gets taught, when it gets taught, or how. Local control as currently practiced obviously isn't working, so maybe it's time to try something different.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)