Except it is. It's basically a punishment detail for having the nerve to be poor. The person I talked with said the work requirement was 35 hours per week between her and her partner. Okay. If a person worked for minimum wage for 35 hours per week, he or she would earn $253.75 before taxes. Figure roughly 4 weeks in a month and you're talking $1015. In Michigan, as of 2014 the average monthly SNAP benefit was $127 per person and $246 per household. If someone has to do community service for over 140 hours per month, that's a pretty steep price to pay for their food stamps. If someone is "earning" their welfare benefit, then they're working for quite literally pennies.

It gets worse. The workfare requirement was originally designed to help people transition into actual jobs. You know, help instill a work ethic. The plan was to push people who were unemployed into finding paying work. Except (and you know there's always an except) when it comes to this community service requirement it doesn't matter if you're one of the unfortunates who qualifies as "working poor." You can be part of a household where one spouse works full-time but the household is large enough and the wage is low enough that you qualify for SNAP. Guess what? The other spouse has to do community service. Workfare will quite literally force a family to put their kids into daycare or incur babysitting costs they otherwise would not need, all in the name of instilling a work ethic in a stay-at-home parent.

Workfare isn't particularly effective at moving people into actual jobs in any case. The organizations where a person is assigned to do their community service generally aren't interested in transitioning anyone into a paying position -- why should they when they've got the labor for free? -- and the work assigned rarely provides any meaningful training or experience. It also isn't effective in reducing the cost of anti-poverty programs. The World Bank, which has an obvious vested interest in supporting workfare, has done a number of studies that show that it's more cost-effective to simply give the poor cash benefits with no strings attached than it is to impose a workfare requirement. But if governments did that the punishment and humiliation aspects would vanish, and that would defeat the real purpose of the programs, which is to make welfare programs so unpleasant that no one applies for them.

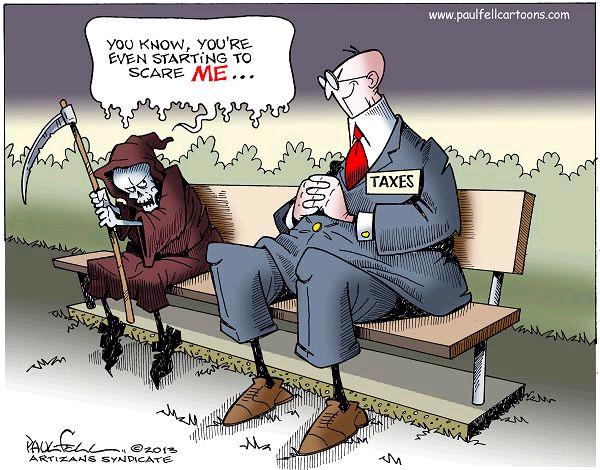

In any case, I might actually buy into the notion of asking benefit recipients to do community service if it was calculated so the hours required matched up with a real world wage, but this bullshit of forcing people to work for pennies? It's dehumanizing, it's devaluing their labor. It's telling the poor they're worthless, or close to it. If their work had any meaning, the program would calculate the hours differently, make it a closer match between a legal wage and the amount they're going to receive. But when it's the equivalent of $1/hour or less? Then it's pretty obvious the work doesn't mean anything; it's the punishment part that's important.

Still, I did not say no to the offer of exploited labor. This is a small rural community; opportunities for community service are limited in number, and I have to give the people credit for having the guts to cold call the museum to ask if they could "volunteer" there. I will feel odd about it, but if it's something they have to do, I'm not going to make things even harder for them. (Side note: one of my pet peeves is the perversion of the word "volunteer." You're not a volunteer if you've been told the activity is required. A more accurate term would be "indentured servant.")

Oddly enough, I had been thinking about talking to the clerk of court to see about getting the other category of community service workers, the ones who end up paying for their DUIs or disorderly conduct by having to pick up trash or wash police cars. The one upside to this is we may get more competent help. With people sentenced to community service by the courts I figure we'd get guys who could do maintenance stuff (sweep, mop, wash windows) but probably not anything more complicated than that. Through workfare, we may end up with a "volunteer" who's computer literate.