The election is several months away, but we've already been experiencing shenanigans at the museum. We have a temporary exhibit this summer, Politics and Voting, and just for the heck of it we decided to put some milk bottles on a table labeled with the four best known candidates' names: Clinton, Trump, Johnson (Libertarian), and Stein (Green Party). The sign tells people to "vote" with their spare change -- in other words, make a tiny donation to the museum.

Knowing that people aren't inclined to toss coins into a totally empty bottle, I salted all four. Each milk jug had $1.50 in assorted coins in it when we opened for the season. I noticed that the level seemed to be climbing fastest in Trump's bottle (something I consider an ominous sign, but that's not the subject of this post). I decided to check to see just what was happening.

As I feared, Trump's bottle had the most coins in it. Both Johnson and Stein had received a few votes, too. But Clinton? This is where shenanigans come in. Not only has no one voted for her, someone's been stealing the "ballots" that were there. She started off with $1.50. As of this afternoon, there's only $1. Not only is she not gaining any votes, she's going backwards.

Random thoughts about roadside art, National Parks, historic preservation, philosophy of technology, and whatever else happens to cross my mind.

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Saturday, July 30, 2016

What is it with Fox News and anger?

I know the feeling. Back in Atlanta when I was working but the S.O. was a man of leisure, he developed this bizarre addiction to CNN. I don't think he had it on all day, but it did seem like he watched way more Wolf Blitzer than any normal human should. In retrospect, I guess it could have been worse. He could have drifted into watching Fox News. Not likely, because we've been calling it Faux News for years, but you never know. A number of my pals are themselves pretty moderate in their political views, basically right in the middle or even slightly to the left in their leanings, as were their spouses, but somehow the men in their lives got seduced by Fox. Maybe it's the lure of all those young, female, blonde news readers. . .

Anyway, it's become apparent that sooner or later if you're a die hard Fox News viewer you slide into being permanently angry. You're pissed off all the time about everything. In the past few years I've gotten a number of letters in which pals describe just how hard it is to live with someone they thought they knew but who has now become a contender in the World's Angriest Man contest. And, as one pal described her significant other's descent into the abyss, it's like the more they watch, the more they have to watch. Her husband used to have hobbies. He golfed. He fished. He puttered around in a workshop. Now he sits, watches Fox News, and rants.

I can understand the news media lying, either through omission (the stories that never get covered) or on purpose. The news media in this country has been doing both for as long as the United States has existed. The idea that the news media are supposed to objective is a fairly recent fantasy. What I don't understand is slanting the news in a way that seems designed to trigger rage on the scale that Fox News does.

Maybe it's just coincidence. Maybe the angry Fox viewer already leaned towards xenophobia, misogyny, and irrational anger and it just took time for that side of their personality to come out. Maybe the spouses were jerks all along, but my pals never noticed during the decades they were both busy with work. Retirement arrives, they're together 24/7, and suddenly it's holy wah, I'm married to a Bill O'Reilly fan!

I don't know. It's another of life's little mysteries. I do know that every time I read one of those letters from a pal wondering what's wrong with her spouse -- is Fox viewing a warning sign for the onset of senile dementia? Does she need to start looking into nursing homes that specialize in memory care? -- I'm relieved my biggest complaint about the S.O. is he's not a morning person.

Sunday, July 24, 2016

Gardening

|

| Potato plant |

It would be nice -- last year the chipmunks wiped out most of the plants just as they started to sprout, and the year before that I think it was drought. Or maybe poor soil. We have one area in the garden where it seems like no matter what we do to it -- compost worked in, commercial fertilizer, treatments to correct the pH, you name it -- nothing wants to grow particularly well. I'm thinking seriously about marking that space off, planting clover there, and letting it stay fallow for a couple years.

I also finally got my baby rhubarb plants set out. Last summer I saved a lot of rhubarb seeds just for the heck of it. You know, almost no one grows rhubarb from seed. The usual method is to divide up an existing clump. That's how all of our rhubarb wound up where it is. We either transplanted existing rhubarb or bought live plants. But when one of the rhubarb plants bloomed last year, I decided to let it go all the way. Usually we cut the flower stalks off, the theory being that you always want the plant to put its energy into its roots and not into seeding, but last year I ignored the nascent stalks, let them flower and seeds form, and then bagged a bunch of the seeds.

Back in May, I planted about a dozen seeds in peat pots with two seeds to a pot. Of all the stuff I started from seed, the rhubarb took the longest to sprout and had the lowest germination rate: only two pots had any seedlings appear. In contrast, when I started zucchini, the rate was 6 out of 6. This helps explain why although the rhubarb plants will have a gazillion seeds, all of which look like they'd travel on the wind pretty good, a person doesn't look around and see our yard being taken over by rhubarb the way oregano and chives have overrun everything (every time we mow the lawn by the Woman Cave I find myself craving Italian food).

|

| Oregano in bloom. Bees love it. |

In any case, there was an empty space in our row of rhubarb so yesterday I planted the two little tiny baby rhubarb plants in that area. Rain was predicted so I figured it would be good to get them in the ground before it rained, not after. I put a marker by each so we won't accidentally smother them when we mulch around the other plants. Now all I have to do is hope they survive. Because we have both kinds of rhubarb in the garden -- red and green -- and both kinds flowered, I'm a little curious to see what the plants end up being. With cross pollination, either is possible.

|

| Rhubarb seeds |

Saturday, July 23, 2016

Some helpful tips if you're planning on donating something -- anything! -- to a museum

Tip Number One: Don't drop off a box of stuff, fail to fill out a detailed donation form, and then return 5 years later expecting someone at the museum to be prepared to give you back anything and everything that was in said container that "the museum didn't need."

But that's what happened today. A lady walked in, asked the volunteers working this afternoon about the items in question, and they called me. I am, after all, the person who plays with the database. In theory, I know where stuff is. But something that got dropped off at least a year before I began volunteering? And that apparently had no documentation?

Definitely a head*desk (or perhaps a head*wall) moment.

It turned out I did recall the box in question. It was sitting in the office when I first began volunteering in June 2012. It had a note on it saying that the historical society's military history expert had gone through it to see if there was anything war-related that the museum could use. The container was waiting for Karen, the museum's volunteer curator for everything else, to look it over. And then what? I don't know. Based on the lack of other instructions, the assumption would be to pitch (or give to St. Vincent de Paul) anything that didn't fit in with the museum's mission. Karen never did get to the box; eventually it became my duty to dig through it.

It turned out to be an interesting mix of stuff, some of which was total trash (old store receipts, for example) and some that was really neat. I sorted, cataloged, and filed. Some artifacts wound up incorporated into exhibits, some went into storage. Documents got sorted into several different categories -- a family history file, World War I, World War II, Boy Scouts, and some others -- and it all got recorded as having been donated by a specific family.

In any case, by the time I was done going through the box, everything that was in it was either something that the museum needed, however need may be defined, or so obviously worthless it went into the trash. There were a few things that had teetered on the line between keep or discard, but when in doubt I opted for keep. Of course, one reason for that clear dichotomy -- catalog or jettison -- was there was no indication I should do otherwise. The container came into the museum in 2011; I didn't start to get into it until at least two years later, possibly 3. There was nothing to indicate it was any different from the other boxes of miscellaneous weirdness we get, the stuff that's left over after the estate sale, the odds and ends a family can't manage to toss in a dumpster themselves so they drop it at the museum instead.

Personally, I find it hard to believe that anyone associated with the museum would have accepted a box full of stuff with the understanding that we were going to look through it, take out a few things, and then hand the rest back given how many boxes of unsorted stuff were already taking up space in the building. I am reasonably sure that if Karen had still been capable of scampering up the ladder to the attic that's where the box would have gone to gather dust indefinitely. I have a hunch that what happened is the lady came in, talked with our now-deceased past president, and the two of them managed to talk past each other. He thought she was giving the museum a no strings attached box of stuff; she thought he understood that at some point she'd be back to pick up whatever the museum didn't want. But we'll never know for sure -- Jim's been dead for over 3 years now.

Bottom line, people, is that you all need to do your sorting first, taking out anything that has any sentimental value for you, and then drop the leftovers at the local historical society. When you do drop it off, make sure you get a receipt, a document that spells out what rights (if any) you retain and what you're giving up. You can't count on people's memories. People die, they stop volunteering, they deal with enough people and donations that everything just blurs together. It was sheer luck that when the volunteer on duty at the museum called me I could actually recall a few details about the box in question. We now have approximately 4,000 artifacts in the database; if I'm pushed, I can remember specifics about maybe a few hundred of them. Or maybe a few dozen. Or maybe six or seven. And those are the ones I did most recently. If it went into the database a year or two ago, odds are that I've forgotten the thing exists. The whole point of the database is that we won't have to rely on people's memories; we can look stuff up.

Finally, if you're considering donating with strings attached, don't do it. Don't assume you can treat the local historical society museum like a storage unit, dropping off your family's tchotchkes for awhile and then coming back a few years later to pick them up because you've had an attack of nostalgia or a delayed inclination to hoard. If you're not willing to abide by the line on the donation form that says once the museum receives an item we can do whatever we want with it -- add it to the collections, put it in an exhibit, give it to another museum, sell it, or throw it away -- then don't donate at all.

But that's what happened today. A lady walked in, asked the volunteers working this afternoon about the items in question, and they called me. I am, after all, the person who plays with the database. In theory, I know where stuff is. But something that got dropped off at least a year before I began volunteering? And that apparently had no documentation?

Definitely a head*desk (or perhaps a head*wall) moment.

It turned out I did recall the box in question. It was sitting in the office when I first began volunteering in June 2012. It had a note on it saying that the historical society's military history expert had gone through it to see if there was anything war-related that the museum could use. The container was waiting for Karen, the museum's volunteer curator for everything else, to look it over. And then what? I don't know. Based on the lack of other instructions, the assumption would be to pitch (or give to St. Vincent de Paul) anything that didn't fit in with the museum's mission. Karen never did get to the box; eventually it became my duty to dig through it.

It turned out to be an interesting mix of stuff, some of which was total trash (old store receipts, for example) and some that was really neat. I sorted, cataloged, and filed. Some artifacts wound up incorporated into exhibits, some went into storage. Documents got sorted into several different categories -- a family history file, World War I, World War II, Boy Scouts, and some others -- and it all got recorded as having been donated by a specific family.

In any case, by the time I was done going through the box, everything that was in it was either something that the museum needed, however need may be defined, or so obviously worthless it went into the trash. There were a few things that had teetered on the line between keep or discard, but when in doubt I opted for keep. Of course, one reason for that clear dichotomy -- catalog or jettison -- was there was no indication I should do otherwise. The container came into the museum in 2011; I didn't start to get into it until at least two years later, possibly 3. There was nothing to indicate it was any different from the other boxes of miscellaneous weirdness we get, the stuff that's left over after the estate sale, the odds and ends a family can't manage to toss in a dumpster themselves so they drop it at the museum instead.

Personally, I find it hard to believe that anyone associated with the museum would have accepted a box full of stuff with the understanding that we were going to look through it, take out a few things, and then hand the rest back given how many boxes of unsorted stuff were already taking up space in the building. I am reasonably sure that if Karen had still been capable of scampering up the ladder to the attic that's where the box would have gone to gather dust indefinitely. I have a hunch that what happened is the lady came in, talked with our now-deceased past president, and the two of them managed to talk past each other. He thought she was giving the museum a no strings attached box of stuff; she thought he understood that at some point she'd be back to pick up whatever the museum didn't want. But we'll never know for sure -- Jim's been dead for over 3 years now.

Bottom line, people, is that you all need to do your sorting first, taking out anything that has any sentimental value for you, and then drop the leftovers at the local historical society. When you do drop it off, make sure you get a receipt, a document that spells out what rights (if any) you retain and what you're giving up. You can't count on people's memories. People die, they stop volunteering, they deal with enough people and donations that everything just blurs together. It was sheer luck that when the volunteer on duty at the museum called me I could actually recall a few details about the box in question. We now have approximately 4,000 artifacts in the database; if I'm pushed, I can remember specifics about maybe a few hundred of them. Or maybe a few dozen. Or maybe six or seven. And those are the ones I did most recently. If it went into the database a year or two ago, odds are that I've forgotten the thing exists. The whole point of the database is that we won't have to rely on people's memories; we can look stuff up.

Finally, if you're considering donating with strings attached, don't do it. Don't assume you can treat the local historical society museum like a storage unit, dropping off your family's tchotchkes for awhile and then coming back a few years later to pick them up because you've had an attack of nostalgia or a delayed inclination to hoard. If you're not willing to abide by the line on the donation form that says once the museum receives an item we can do whatever we want with it -- add it to the collections, put it in an exhibit, give it to another museum, sell it, or throw it away -- then don't donate at all.

Friday, July 22, 2016

Book Review: The Gift of Fear

I missed this book when it first came out almost 20 years ago, but my favorite advice columnist, Carolyn Hax, recommends it on a regular basis. When I spotted it at the library the other day, I decided it was time to finally read it. I'm glad I did.

The bottom line in this book is trust your gut. If your instincts tell you something isn't right, listen. We humans spend our entire lives being socially conditioned to deny and ignore basic survival instincts. We'll deny the obvious -- the warning signs that a new boyfriend is a controlling abuser, that a problem employee has the potential for violence, that the nice young man who's offered to help carry your groceries is planning to mug you in the parking lot. Women especially are trained from childhood to be "nice," to never make a fuss, not to be aggressive. We're so afraid of looking like a bitch that we set ourselves up to be abused. We'll try to explain away or make excuses for people showing every clear sign that they're borderline crazy or worse.

De Becker does notes that although women have been trained by society to ignore warning signs, men can be just as bad when it comes to denial in settings like the workplace. Employees will signal loud and clear that they're a serious risk to have around, but managers will ignore warning sign after warning sign until it's too late. De Becker gives multiple examples of incidents that were easily preventable if employers had just taken the time to actually do background checks, to ask serious questions at job interviews, or to take complaints from other employees seriously. When he asked employers why they didn't check references, the excuse was that they knew that no one would provide a reference who was going to give a bad answer. Well, it might still be a good idea to verify that the references actually exist or that the applicant did work at the places given as past employers. At the very least, discovering that an applicant claimed to have worked for a company that doesn't exist would be a clue that applicant might not be the most honest person on the planet.

A slight digression: I am always astounded when I read about cases where people have managed to lie their way into some fairly high profile jobs by giving themselves degrees from colleges they never attended or listing past employers who don't exist. Yes, it's true that most employers fear litigation enough that they won't say anything negative about a former employee, but they will at least tell you whether or not someone actually worked for them. And you know what? If you call a former employer and the reaction on the phone involves an audible gasp and a muttered "Oh, shit. . ." before they go into the spiel about not being able to say anything other than to confirm employment you've gotten the answer you needed.

Anyway, De Becker also mentions that communications within a company can lead to problems going unresolved and eventually exploding. If top management doesn't know a problem exists, they can't address it. He gives an example using sexual harassment in the workplace: when he talked with a CEO of a national restaurant chain, the executive said they had maybe one or two complaints nationally per year. When he went down a level, the number of known complaints went up to a dozen or more. At even lower level, it went from "one or two" to "20 or more a month." Which, of course, meant that nation-wide there were hundreds of complaints annually that top management either didn't know about or were pretending didn't exist. Why didn't the guy at the top know what was actually going on? Because no one wanted to be the person reporting bad news. Which isn't much of a shock, actually, considering that CBS Television built a reality series, Undercover Boss, around the premise that the CEO of a corporation has no clue as to what's happening down in trenches.

As I was reading this book, I found myself remembering an episode on Michael Moore's short-lived television series, TV Nation. One of the classic themes when a serial killer is apprehended or some horrific episode of domestic violence occurs is "He seemed like such a nice guy. We never noticed anything unusual." Moore decided to test that. If I recall correctly, he rented a house in a nice suburban neighborhood and then had the male occupant behave in a blatantly suspicious manner, right down to digging large, coffin-sized holes in the backyard and burying human-sized bundles and 55-gallon barrels. After a few weeks, the "police" staged a dramatic raid and marched the occupant out in handcuffs and drove him away. Moore then interviewed the neighbors, who quite predictably

claimed the occupant "seemed like a nice guy" and "never did anything unusual." The occupant had done everything short of putting a billboard in the front yard proclaiming "I'm a serial killer!!" but the neighbors willfully ignored it all.

Part of that willful ignorance no doubt came from the classic American reluctance to get involved, but another motivation had to be denial: denial that there could be a real problem right down the street from where a person lived. Humans are really good at believing that if they just ignore something long enough, it will eventually go away. After all, serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer's landlord bought the explanation that the foul stench coming from Dahmer's apartment was caused by a few dead tropical fish in the trash. Having experienced the Woman Cave becoming unbearable from the stench of one dead mouse, I don't want to think about what a building would smell like with a couple of decaying human cadavers in it. You've got to work hard at denying reality to be able to rationalize away that sort of stench.

De Becker also debunks the notion that violent behavior is not predictable. He lays it out pretty clearly that in domestic violence cases there's always a pattern of escalation. More importantly, he describes the warning signs, the indicators, that signal early on in a relationship that a person is on track to be an abuser.

So what's the bottom line on the book? It's worth reading, especially for its message that there's a difference to living in fear and listening to fear. As Americans we tend to do the first -- too many people live in a constant state of terror, scared silly of abstract stuff that's never going to happen, while ignoring our intuition about threats that are right in front of us. We tie ourselves in emotional knots about threats from terrorists while ignoring the nagging sense that there's something about a potential babysitter or boyfriend that doesn't seem quite right. Then we're shocked when the babysitter turns out to be a thief or the boyfriend becomes violent.

Because the edition I read came out in 1998, when social media as we know it now did not exist and cell phones were still relatively rare, I wondered if there was an updated edition. Apparently not. However, that's a minor quibble. It would be interesting to see De Becker's thoughts on dealing with social media, most of which strike me as being a stalker's dream come true, but the fact it's not discussed in the book doesn't make the book overall less important.

The bottom line in this book is trust your gut. If your instincts tell you something isn't right, listen. We humans spend our entire lives being socially conditioned to deny and ignore basic survival instincts. We'll deny the obvious -- the warning signs that a new boyfriend is a controlling abuser, that a problem employee has the potential for violence, that the nice young man who's offered to help carry your groceries is planning to mug you in the parking lot. Women especially are trained from childhood to be "nice," to never make a fuss, not to be aggressive. We're so afraid of looking like a bitch that we set ourselves up to be abused. We'll try to explain away or make excuses for people showing every clear sign that they're borderline crazy or worse.

De Becker does notes that although women have been trained by society to ignore warning signs, men can be just as bad when it comes to denial in settings like the workplace. Employees will signal loud and clear that they're a serious risk to have around, but managers will ignore warning sign after warning sign until it's too late. De Becker gives multiple examples of incidents that were easily preventable if employers had just taken the time to actually do background checks, to ask serious questions at job interviews, or to take complaints from other employees seriously. When he asked employers why they didn't check references, the excuse was that they knew that no one would provide a reference who was going to give a bad answer. Well, it might still be a good idea to verify that the references actually exist or that the applicant did work at the places given as past employers. At the very least, discovering that an applicant claimed to have worked for a company that doesn't exist would be a clue that applicant might not be the most honest person on the planet.

A slight digression: I am always astounded when I read about cases where people have managed to lie their way into some fairly high profile jobs by giving themselves degrees from colleges they never attended or listing past employers who don't exist. Yes, it's true that most employers fear litigation enough that they won't say anything negative about a former employee, but they will at least tell you whether or not someone actually worked for them. And you know what? If you call a former employer and the reaction on the phone involves an audible gasp and a muttered "Oh, shit. . ." before they go into the spiel about not being able to say anything other than to confirm employment you've gotten the answer you needed.

Anyway, De Becker also mentions that communications within a company can lead to problems going unresolved and eventually exploding. If top management doesn't know a problem exists, they can't address it. He gives an example using sexual harassment in the workplace: when he talked with a CEO of a national restaurant chain, the executive said they had maybe one or two complaints nationally per year. When he went down a level, the number of known complaints went up to a dozen or more. At even lower level, it went from "one or two" to "20 or more a month." Which, of course, meant that nation-wide there were hundreds of complaints annually that top management either didn't know about or were pretending didn't exist. Why didn't the guy at the top know what was actually going on? Because no one wanted to be the person reporting bad news. Which isn't much of a shock, actually, considering that CBS Television built a reality series, Undercover Boss, around the premise that the CEO of a corporation has no clue as to what's happening down in trenches.

As I was reading this book, I found myself remembering an episode on Michael Moore's short-lived television series, TV Nation. One of the classic themes when a serial killer is apprehended or some horrific episode of domestic violence occurs is "He seemed like such a nice guy. We never noticed anything unusual." Moore decided to test that. If I recall correctly, he rented a house in a nice suburban neighborhood and then had the male occupant behave in a blatantly suspicious manner, right down to digging large, coffin-sized holes in the backyard and burying human-sized bundles and 55-gallon barrels. After a few weeks, the "police" staged a dramatic raid and marched the occupant out in handcuffs and drove him away. Moore then interviewed the neighbors, who quite predictably

claimed the occupant "seemed like a nice guy" and "never did anything unusual." The occupant had done everything short of putting a billboard in the front yard proclaiming "I'm a serial killer!!" but the neighbors willfully ignored it all.

Part of that willful ignorance no doubt came from the classic American reluctance to get involved, but another motivation had to be denial: denial that there could be a real problem right down the street from where a person lived. Humans are really good at believing that if they just ignore something long enough, it will eventually go away. After all, serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer's landlord bought the explanation that the foul stench coming from Dahmer's apartment was caused by a few dead tropical fish in the trash. Having experienced the Woman Cave becoming unbearable from the stench of one dead mouse, I don't want to think about what a building would smell like with a couple of decaying human cadavers in it. You've got to work hard at denying reality to be able to rationalize away that sort of stench.

De Becker also debunks the notion that violent behavior is not predictable. He lays it out pretty clearly that in domestic violence cases there's always a pattern of escalation. More importantly, he describes the warning signs, the indicators, that signal early on in a relationship that a person is on track to be an abuser.

So what's the bottom line on the book? It's worth reading, especially for its message that there's a difference to living in fear and listening to fear. As Americans we tend to do the first -- too many people live in a constant state of terror, scared silly of abstract stuff that's never going to happen, while ignoring our intuition about threats that are right in front of us. We tie ourselves in emotional knots about threats from terrorists while ignoring the nagging sense that there's something about a potential babysitter or boyfriend that doesn't seem quite right. Then we're shocked when the babysitter turns out to be a thief or the boyfriend becomes violent.

Because the edition I read came out in 1998, when social media as we know it now did not exist and cell phones were still relatively rare, I wondered if there was an updated edition. Apparently not. However, that's a minor quibble. It would be interesting to see De Becker's thoughts on dealing with social media, most of which strike me as being a stalker's dream come true, but the fact it's not discussed in the book doesn't make the book overall less important.

Thursday, July 14, 2016

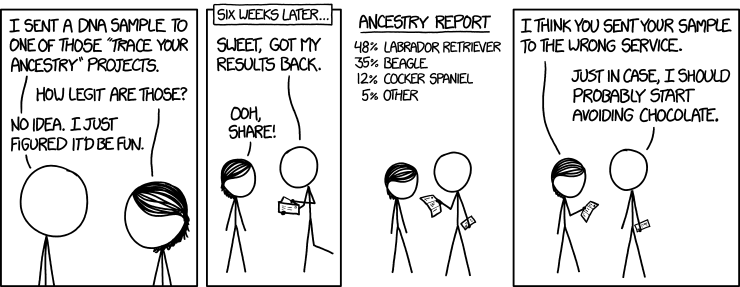

Wondering about one's ancestry

We get a lot of requests at the museum for genealogy research. Every so often I'll end up talking with someone who's gone one step farther than just building family trees and spent money on DNA testing. One of my acquaintances, a sort of cousin, did that and ever since has bored the rest of us with her wondering out loud how she happened to end up with a high percentage of Azkhenazi Jewish genes when she thought the family tree was packed solid with Finnish Lutherans. I don't get the point of obsessing about it, unless she's planning to try to persuade the country of Israel that she's entitled to the right of return, but then I don't understand the simpler obsession with ancestry either. In any case, I figure that if I ever were foolish enough to spend money on DNA testing, this is the type of result I'd get.

Except mine would come back with a significant percentage of border collie instead of beagle.

Except mine would come back with a significant percentage of border collie instead of beagle.

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

What's new at the museum, you ask?

Our hose cart is done.

Regular readers (all two of you) may recall that last summer I vowed that the fire hose cart would be repaired and repainted before it went back into the storage building for the winter.

I lied. I did get some Bondo (aka wood putty) on to it and one wheel looking moderately less sad, but that was as far as I got. Then this spring we placed an ad a Facebook page, Baraga County Stuff for Sale (No Clothes), seeking a handyman willing to finish staining the new siding on the museum. A fellow answered the ad who said he'd worked for a local company that does painting but had had to stop working for awhile when his mother became ill. He seemed to know what he was talking about when it came to paint, so we contracted with him. We settled on a lump sum for the job, and he went to work.

Even before it was done, we were thinking, wow, this guy really does know what he's doing. Among other things, he was the neatest painter I'd ever seen. There were no splatters on the ground, no paint on his clothes. It was amazing. So I asked him to look over the fire hose cart and see if he felt comfortable rehabbing it. He looked it over. He said yes. Because it was obviously a lot harder to estimate how long it would take to do the hose cart, we opted for a contract that's based on hours worked and not a lump sum.

The hose cart is now done. It looks great. He's moved on to rehabbing our Railway Express freight cart. I have no doubt it's going to look great, too. I have to confess I find myself casting about trying to figure out other painting/rehabbing projects for Dave to tackle, but unfortunately can't think of any. Which is probably good for the museum's budget, but, still. . . when he's being doing such a great job, I hate to see him leave.

|

| The fire hose cart. It came from the Ford company town of Alberta. We've got about 40 feet of hose on the cart; I'd like to have more. |

Regular readers (all two of you) may recall that last summer I vowed that the fire hose cart would be repaired and repainted before it went back into the storage building for the winter.

|

| The cart was designed to be pulled by the firemen but at some point was modified so it could be towed by vehicle. |

I lied. I did get some Bondo (aka wood putty) on to it and one wheel looking moderately less sad, but that was as far as I got. Then this spring we placed an ad a Facebook page, Baraga County Stuff for Sale (No Clothes), seeking a handyman willing to finish staining the new siding on the museum. A fellow answered the ad who said he'd worked for a local company that does painting but had had to stop working for awhile when his mother became ill. He seemed to know what he was talking about when it came to paint, so we contracted with him. We settled on a lump sum for the job, and he went to work.

Even before it was done, we were thinking, wow, this guy really does know what he's doing. Among other things, he was the neatest painter I'd ever seen. There were no splatters on the ground, no paint on his clothes. It was amazing. So I asked him to look over the fire hose cart and see if he felt comfortable rehabbing it. He looked it over. He said yes. Because it was obviously a lot harder to estimate how long it would take to do the hose cart, we opted for a contract that's based on hours worked and not a lump sum.

|

| Our Railway Express cart. It came from the L'Anse depot and was in really sad shape before Dave started working on it. |

The hose cart is now done. It looks great. He's moved on to rehabbing our Railway Express freight cart. I have no doubt it's going to look great, too. I have to confess I find myself casting about trying to figure out other painting/rehabbing projects for Dave to tackle, but unfortunately can't think of any. Which is probably good for the museum's budget, but, still. . . when he's being doing such a great job, I hate to see him leave.

|

| The freight cart is going to stay on jack stands after it's done so there's no weight on the wheels. We should put the hose cart on a stand, too, but it's trickier because the axle is lot higher. |

Monday, July 11, 2016

Confession time. Cops scare me.

And if a 68-year-old white woman views the boys in blue with a fair amount of trepidation, is it any surprise minorities aren't too thrilled with them? I've always been a bit skeptical regarding the police, having witnessed a few too many examples of power-tripping sociopaths ending up wearing a badge, but have become even more so in recent years. I'm not sure why I remain skeptical. After all, I have friends who work in law enforcement (or are now retired from it) and they're decent people. I also know that the majority of cops went into law enforcement for the right reasons . . . but I guess I worry that even if 99 out of 100 are upright, ethical people who'd never ever abuse their position, my encounter will be with the 1 percenter who's a flaming asshat just waiting for someone powerless to abuse.

You know the ones I mean. The traffic cop who ignores the Porsche doing 100 in a 35 mph zone but is all over the poor sap driving a beater of a '92 Impala with a burnt-out tail light. The cop who gets off on ticketing college students for being drunk in public when they're walking home from a party and happen to stumble or weave a little. The cop who shoots your dog instead of just reminding you about local leash laws. The cop who tells teenage girls he won't arrest them for being minors in possession if they'll just give him an occasional blow job. Or the cop who's been harboring fantasies of going all Rambo and emptying a clip into someone for years. Because those guys (and gals; not all power-tripping asshats are men) are out there. They've been out there for years and they're going to stay out there because as a profession law enforcement has done a piss poor job of policing itself.

Don't believe me? Suggest to almost anyone who's currently in law enforcement that some of their brother officers might be better off in a different career and they'll freak out as they go into full-blown denial mode.With a few rare exceptions they'll swear up and down that every single LEO they have ever known was a fine, decent human being who never took advantage of wearing a badge. The same people who may have confided to non-law enforcement friends that they didn't think the latest addition to the force should have been hired -- "She's got a real cowboy mentality, seems to get off on civilians being afraid of her" -- will close ranks in a New York minute if a non-LEO says something negative.

In any case, what I have noticed in recent years is the way law enforcement seems to have slid from being part of the community, any community, to being at war with the rest of the world. There's a distinct Us (the Police) versus Them (the general public) attitude that's becoming more and more noticeable. And I'm not the only one noticing. It's been coming up as a theme in various articles I've read (both op-ed pieces and in scholarly research) and I've heard it a lot in the past few days on different talk shows on NPR and Sirius XM. And most of the people saying it are law enforcement professionals, men and women who have been wearing a badge for decades.

I saw an intriguing meme on Facebook the other day, one that I wish I had downloaded at the time, that used a dead canary in a coal mine analogy. In the past few years, there's been more and more focus on the racial bias apparent in the excessive use of force by the police -- blacks comprise a disproportionate number of persons killed annually by the police in the United States. But they're not the only ones being killed. They're "only" 26 percent of the victims. So who makes up the other 74%? Mostly white people, because whites are still the majority population in this country. We hear about the white guys who get treated with the proverbial kid gloves: mass murderer Dylann Roof being treated to takeout from Burger King or an armed white supremacist schmoozing cheerfully with the police. We don't hear about the ones who aren't that lucky. Which is another way of saying that the black victims of police violence are the canaries in the coal mine, the most visible evidence that something is wrong.

Maybe, just maybe, it would behoove all of us, including the racist asshats who assume that any time someone black ends up dead he or she deserved it, to take a long hard look at just what's going on in police departments that leads to them shooting over 1,000 people (on average) annually. Especially when the studies that have been done indicate that at least 20 percent of the persons shot were unarmed. You got it. Unarmed. No weapons of any sort, no gun, no knife, nada. Lots and lots of cops falling back on the old "I thought the suspect was reaching for a gun" line.

Once again, there is a strong racial bias -- blacks are a lot more likely to get shot while unarmed -- but whites do get shot, too. Police brutality may not be equal opportunity, but it can hit anyone anywhere regardless of race, gender, or even age. The cops have killed some remarkably old people -- unless a geezer is armed with an Uzi, how much of a threat can an octogenarian be? Apparently a serious one because the police haven't hesitated to use lethal force on the elderly. (Side note: while we were living in Atlanta, the cops shot and killed a lady who was in her 90s. Turned out they were at the wrong address because of a bad tip from an informant, didn't clearly identify themselves, and the old lady tried to defend herself from what she thought was a home invasion. Maybe she did have an Uzi. Or maybe someone in the Atlanta PD should have done a little more research before kicking in her front door.)

At the same time, we're seeing an increasing militarization of the police: more heavy weapons, armored vehicles, the use of SWAT to respond to calls that used to involve maybe one pair of police officers (e.g., noise complaints). Any time you have a heavy handed response to what used to be a minor issue, you're doing two things: you're increasing the likelihood of something going wrong and you're training the populace to see the police as the enemy. Toss in police recruiting ads designed to attract warrior personalities and active recruitment of military veterans and what do you have? Individual law enforcement officers who view every civilian as a potential threat -- we're not citizens; we're potential enemy combatants -- and police departments that behave like occupying armies. A recent issue of the VFW magazine lauded veterans who work in law enforcement. I'm not sure that's such a good thing.

Why? Most of those veterans going into law enforcement now have spent time in combat zones like Iraq and Afghanistan. Some have done multiple tours of duty. Well, if you've spent a couple of years being conditioned to view every person you see who isn't in a U.S. military uniform as a potential threat, how fast are you going to shed that mentality when you get home? Good question. Maybe never.

So, yes, cops scare me and they'll keep on scaring me as long as it looks like they're getting away with murder. When I start reading more news reports about LEOs being disciplined for kicking in the wrong doors or shooting the wrong people, my skepticism may wane. And by disciplined, I mean actual punishment, not just a few weeks or months of desk duty and then back out in the streets to repeat whatever stupid thing they did to begin with. Until then? I don't think so.

You know the ones I mean. The traffic cop who ignores the Porsche doing 100 in a 35 mph zone but is all over the poor sap driving a beater of a '92 Impala with a burnt-out tail light. The cop who gets off on ticketing college students for being drunk in public when they're walking home from a party and happen to stumble or weave a little. The cop who shoots your dog instead of just reminding you about local leash laws. The cop who tells teenage girls he won't arrest them for being minors in possession if they'll just give him an occasional blow job. Or the cop who's been harboring fantasies of going all Rambo and emptying a clip into someone for years. Because those guys (and gals; not all power-tripping asshats are men) are out there. They've been out there for years and they're going to stay out there because as a profession law enforcement has done a piss poor job of policing itself.

Don't believe me? Suggest to almost anyone who's currently in law enforcement that some of their brother officers might be better off in a different career and they'll freak out as they go into full-blown denial mode.With a few rare exceptions they'll swear up and down that every single LEO they have ever known was a fine, decent human being who never took advantage of wearing a badge. The same people who may have confided to non-law enforcement friends that they didn't think the latest addition to the force should have been hired -- "She's got a real cowboy mentality, seems to get off on civilians being afraid of her" -- will close ranks in a New York minute if a non-LEO says something negative.

In any case, what I have noticed in recent years is the way law enforcement seems to have slid from being part of the community, any community, to being at war with the rest of the world. There's a distinct Us (the Police) versus Them (the general public) attitude that's becoming more and more noticeable. And I'm not the only one noticing. It's been coming up as a theme in various articles I've read (both op-ed pieces and in scholarly research) and I've heard it a lot in the past few days on different talk shows on NPR and Sirius XM. And most of the people saying it are law enforcement professionals, men and women who have been wearing a badge for decades.

I saw an intriguing meme on Facebook the other day, one that I wish I had downloaded at the time, that used a dead canary in a coal mine analogy. In the past few years, there's been more and more focus on the racial bias apparent in the excessive use of force by the police -- blacks comprise a disproportionate number of persons killed annually by the police in the United States. But they're not the only ones being killed. They're "only" 26 percent of the victims. So who makes up the other 74%? Mostly white people, because whites are still the majority population in this country. We hear about the white guys who get treated with the proverbial kid gloves: mass murderer Dylann Roof being treated to takeout from Burger King or an armed white supremacist schmoozing cheerfully with the police. We don't hear about the ones who aren't that lucky. Which is another way of saying that the black victims of police violence are the canaries in the coal mine, the most visible evidence that something is wrong.

Maybe, just maybe, it would behoove all of us, including the racist asshats who assume that any time someone black ends up dead he or she deserved it, to take a long hard look at just what's going on in police departments that leads to them shooting over 1,000 people (on average) annually. Especially when the studies that have been done indicate that at least 20 percent of the persons shot were unarmed. You got it. Unarmed. No weapons of any sort, no gun, no knife, nada. Lots and lots of cops falling back on the old "I thought the suspect was reaching for a gun" line.

Once again, there is a strong racial bias -- blacks are a lot more likely to get shot while unarmed -- but whites do get shot, too. Police brutality may not be equal opportunity, but it can hit anyone anywhere regardless of race, gender, or even age. The cops have killed some remarkably old people -- unless a geezer is armed with an Uzi, how much of a threat can an octogenarian be? Apparently a serious one because the police haven't hesitated to use lethal force on the elderly. (Side note: while we were living in Atlanta, the cops shot and killed a lady who was in her 90s. Turned out they were at the wrong address because of a bad tip from an informant, didn't clearly identify themselves, and the old lady tried to defend herself from what she thought was a home invasion. Maybe she did have an Uzi. Or maybe someone in the Atlanta PD should have done a little more research before kicking in her front door.)

At the same time, we're seeing an increasing militarization of the police: more heavy weapons, armored vehicles, the use of SWAT to respond to calls that used to involve maybe one pair of police officers (e.g., noise complaints). Any time you have a heavy handed response to what used to be a minor issue, you're doing two things: you're increasing the likelihood of something going wrong and you're training the populace to see the police as the enemy. Toss in police recruiting ads designed to attract warrior personalities and active recruitment of military veterans and what do you have? Individual law enforcement officers who view every civilian as a potential threat -- we're not citizens; we're potential enemy combatants -- and police departments that behave like occupying armies. A recent issue of the VFW magazine lauded veterans who work in law enforcement. I'm not sure that's such a good thing.

Why? Most of those veterans going into law enforcement now have spent time in combat zones like Iraq and Afghanistan. Some have done multiple tours of duty. Well, if you've spent a couple of years being conditioned to view every person you see who isn't in a U.S. military uniform as a potential threat, how fast are you going to shed that mentality when you get home? Good question. Maybe never.

So, yes, cops scare me and they'll keep on scaring me as long as it looks like they're getting away with murder. When I start reading more news reports about LEOs being disciplined for kicking in the wrong doors or shooting the wrong people, my skepticism may wane. And by disciplined, I mean actual punishment, not just a few weeks or months of desk duty and then back out in the streets to repeat whatever stupid thing they did to begin with. Until then? I don't think so.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

Sunday, July 3, 2016

Effigy Mounds National Monument

I realized the other day that I never got around to posting anything about our visit two months ago to Effigy Mounds National Monument. Effigy Mounds was the main reason we spent a couple days in southwest Wisconsin on our way home in May.

The park is actually located in Iowa just north of the town of Marquette, but is directly across the Mississippi from Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. It's an interesting place. Native American peoples inhabited the river valley for thousands of years. Over the centuries, they constructed multiple mounds on the top of the bluffs that overlook the river.

It really had me wondering what the area between the Iowa and Wisconsin sides was like before the Corps of Engineers began messing with the river. Thanks to the string of locks and dams that have channelized the Mississippi, in the area near Prairie du Chien there isn't much land between the water and the high ground. That wouldn't have been true when the mound building cultures were at their peak. How much archeological evidence was lost when the dams went in, how many village sites wound up under water? We'll never know.

The Wisconsin side is lower than the Iowa side, so a person does wonder just what motivated the mound builders to locate their burial mounds where they did: at the top of the bluffs. There had to have been a religious reason; it couldn't have just been that they didn't want to waste the river bottoms, the level ground good for growing corn and squash, on cemetery space. For sure they put some thought into it because the hike up from the river level isn't fast or easy. The bluffs are steep; in places it's a sheer drop-off.

You do a lot of walking, switch-backing up the side of a pretty steep hill for quite a ways, before you get to the top and the level where the most impressive mounds are located.

It is, of course, really hard to photograph mounds when you're standing next to them. You can tell it's a mound when you're right there staring at it, but you don't get much of a sense of what it's like when you look at a ground-level photo later.

Effigy Mounds gets its name from the fact that not only does it have a lot of mounds, quite a few of them are in distinct shapes, primarily bears. Or at least quadrupeds that look an awful lot like bears. There are a lot of small bear mounds, one medium size bear mound, and one humongous bear mound. Are they actually representations of bears? Good question, but they look more like bears than anything else so it seems like an appropriate label.

The park's visitor center has a small museum and provides quite a bit of information about the history of the site and what's known about it. The mounds did experience the usual looting that most of the highly visible (and mounds are pretty noticeable) sites have been subjected to, some of which was actually fairly recent. There was a bizarre scandal in 2015 when a former park superintendent who had been retired for almost 20 years decided to return a box containing human remains. He'd had it stashed in his garage. I'd love to know how he got the bones in the first place (stole them from the park's collections rather than comply with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act when it was passed a couple decades ago?), but who knows? Definitely an odd story, but not relevant to current park management or the typical visitor experience.

In any case, I thought the exhibits were nicely done considering it's not a very large space. I suffered my usual plexiglass envy -- every time I visit a museum that enjoys a better budget or has benefited from professional design services I find myself fantasizing about ways to keep visitors from being able to touch the stuff in the Baraga County Historical Museum -- as well as admiring the curation. I'm always blown away by the way museum professionals can take a minimal amount of material, set it up in a pretty small display area, and make it interesting.

I can see making a return trip to Effigy Mounds if we're ever in the area. We only walked one trail so did not see everything -- and even if we had, it's a nice peaceful place to pause for a few hours or even a full day. If you do the longest loop, you end up walking about 7 miles. The trails are wide and well maintained. If it wasn't for the hill climb, I'd describe them as easy, almost accessible, but the steepness of the grade might push them into the moderate category.

|

| Sign reminding park visitors to be respectful and to not indulge in looting. |

|

| Looking downriver toward Marquette, Iowa. |

It really had me wondering what the area between the Iowa and Wisconsin sides was like before the Corps of Engineers began messing with the river. Thanks to the string of locks and dams that have channelized the Mississippi, in the area near Prairie du Chien there isn't much land between the water and the high ground. That wouldn't have been true when the mound building cultures were at their peak. How much archeological evidence was lost when the dams went in, how many village sites wound up under water? We'll never know.

|

| The trail has multiple switchbacks similar to this one. It takes awhile to get to the top. |

The Wisconsin side is lower than the Iowa side, so a person does wonder just what motivated the mound builders to locate their burial mounds where they did: at the top of the bluffs. There had to have been a religious reason; it couldn't have just been that they didn't want to waste the river bottoms, the level ground good for growing corn and squash, on cemetery space. For sure they put some thought into it because the hike up from the river level isn't fast or easy. The bluffs are steep; in places it's a sheer drop-off.

|

| The S.O. ignoring a sign reminding people they're at danger of falling a long, long way if they're not careful. |

|

| People can't read. There were social trails made by people who had decided they didn't have the patience for switchbacks either on the way up or, more likely, the way down. |

It is, of course, really hard to photograph mounds when you're standing next to them. You can tell it's a mound when you're right there staring at it, but you don't get much of a sense of what it's like when you look at a ground-level photo later.

|

| The mound to the left of the trail is roughly circular in shape. It's one of a line of circular mounds. |

|

| It really does look like a bear when you're standing next to it. |

|

| One of the overlooks along the trail. |

In any case, I thought the exhibits were nicely done considering it's not a very large space. I suffered my usual plexiglass envy -- every time I visit a museum that enjoys a better budget or has benefited from professional design services I find myself fantasizing about ways to keep visitors from being able to touch the stuff in the Baraga County Historical Museum -- as well as admiring the curation. I'm always blown away by the way museum professionals can take a minimal amount of material, set it up in a pretty small display area, and make it interesting.

I can see making a return trip to Effigy Mounds if we're ever in the area. We only walked one trail so did not see everything -- and even if we had, it's a nice peaceful place to pause for a few hours or even a full day. If you do the longest loop, you end up walking about 7 miles. The trails are wide and well maintained. If it wasn't for the hill climb, I'd describe them as easy, almost accessible, but the steepness of the grade might push them into the moderate category.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)